Tashlich (תשליך) is a ritual that many Jews observe during the High Holidays.

"Tashlich" means "casting off" in Hebrew and involves symbolically

casting off the sins of the previous year by tossing pieces of bread or

another food into a body of flowing water. Just as the water carries

away the bits of bread, so too are sins symbolically carried away. In

this way the participant hopes to start the New Year with a clean slate.

Vicki Polin is an award winning, retired Licensed Clinical Professional Counselor, who has been working in the anti-rape field since 1985. This blog reflects some of her past work, and contains articles and other information dear to her heart.

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

Saturday, May 26, 2012

Monday, April 30, 2012

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

Thanksgiving: Survivors of child sexual abuse of yesterday, today and tomorrow

By Vicki Polin

Examiner - November 9, 2011

For many families in the United States who celebrate Thanksgiving, it is time of year filled with wonderful memories of families getting together.

Thanksgiving (like any other holiday) often mean that families get together, routines are changed, and there is also the added stress of cleaning and preparing meals. These issues alone can be extremely stress-producing. Unfortunately the reality is that there are parents who are already inclined to use their children as an outlet for emotions and urges, and they are more likely to do so when under the pressure of increased anxiety. Needless to say, many adult survivors of childhood abuse report that their abuse became more intense around and during holidays. For that reason we are asking everyone to say a prayer for the children and their family members, so they get the help they need.

I'm personally asking that each person who reads this article promise to make a phone call, if you suspect a child is either being abused and or neglected, please give that child the gift of a lifetime by calling your local child abuse hot-line regarding your suspicions. Doing so may help prevent any further harm, and it can often lead to a whole family receiving the help and healing that are needed to end the cycle of abuse.

Thanksgiving is a time of year when adult survivors of childhood abuse (emotional, physical and sexual abuse) may be faced with the challenge of deciding if they should go home for the holidays, spend it with friends, or be alone. It is also a time of year for many to have a flood of painful memories reemerge. Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) may increase. It is not uncommon for survivors to find it safer to retreat than to participate in holiday functions.

Each individual survivor needs to figure out what works best for them to stay emotionally healthy. It is critical for survivors to be kind to themselves with whatever decisions they make regarding where they choose to spend Thanksgiving: be it with family, friends, or alone. We all need to respect their decisions, especially if a survivors decide not to celebrate.

To reiterate, it is important to be aware that it is not uncommon for symptoms of PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) to emerge even after times of relative remission and/or intensify in those already struggling. Survivors may experience an increase in disturbing thoughts, nightmares and flashbacks. Thoughts of self-harm, even suicide may be an issue. The important thing to remember is these feelings are about the past, that the abuse is over, and that it is of utmost importance for you to be kind to and gentle with yourself.

This is written as a reminder to all survivors: YOU ARE NOT ALONE!

If you know someone who is a survivor of childhood abuse (emotional, physical and sexual abuse), it might be a good idea to check up on them a few times over the holidays. Make sure survivors have invitation to thanksgiving dinner, and that if they say no, let them know they can always change their mind and come at the last minute.

Over the years we've spoken to many adult survivors who find it very painful to even consider going to anyone's home for the holiday. Maybe this is true for you, too. It is OK. Someday you may feel different, but if the pain is too intense, it is important that you do things that feel healing to you, it is important that you set boundaries to do what feels safe for you.

Remember that whatever works for you is OK: you are not alone in this struggle, not wrong, not bad for having second and third and forth thoughts about how to celebrate and even whether to celebrate the holiday. Look into yourself and see what you need, than do what you can to do it and be kind to yourself for needing to make these adjustments.

To those of you who are survivors . . . thank you so much for Surviving!

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Sunday, September 25, 2011

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Letters to the Editor - Gafni

Letters to the Editor - Gafni

Zeek Magazine - September 21, 2011

Prior to Gafni’s abusive behavior at Bayit Chadash, back in the 1980s,

Mordechai Winiartz (AKA: Marc Gafni), sexually assaulted two teenage

girls. At the time that Judy, one of the teenage girls came and ask for

help. The response from modern orthodox community associated with

Yeshiva University in which Gafni was involved, did what they thought

was best, and chased him out of town.

Back in 2004 the story of the teenage girls went public. The response by many was to shoot the messenger of the dangers of Gafni. Rabbis Saul Berman, Joseph Telushkin and the rest of their gang went on a vicious attack against anyone associated with The Awareness Center. Berman gang member Rabbi Arthur Green, wrote the notorious letter to the editor of the Jewish Week (Abhorrent Column). Green called those of us who were attempting to protect others from being harmed a “rodef”. A person who meets the definition is subject to death.

“He has been relentlessly persecuted for those deeds by a small band of fanatically committed rodfim, in whom proper disapproval of those misdeeds combines with jealously, anger at his swerving from Orthodoxy, and a range of other emotions.)”

The denial of Berman, Telushkin, Green is no different then those at Bayit Chadash or those connected to the world of Diane Hamilton. The reality is that Gafni has been chased out of many different communities over the years -- and the odds are this sexual predator will not be stopped. His modus operandi is to seek out and sexually manipulate beautiful, brilliant woman. After he is caught he lays low for a few years, during which time he recreates himself and professes his innocence and tells his new community that he is wrongly being accused, even though in the past he confessed to clergy sexual abuse against two teenage girls and many adult women.

Back in 2004 the story of the teenage girls went public. The response by many was to shoot the messenger of the dangers of Gafni. Rabbis Saul Berman, Joseph Telushkin and the rest of their gang went on a vicious attack against anyone associated with The Awareness Center. Berman gang member Rabbi Arthur Green, wrote the notorious letter to the editor of the Jewish Week (Abhorrent Column). Green called those of us who were attempting to protect others from being harmed a “rodef”. A person who meets the definition is subject to death.

“He has been relentlessly persecuted for those deeds by a small band of fanatically committed rodfim, in whom proper disapproval of those misdeeds combines with jealously, anger at his swerving from Orthodoxy, and a range of other emotions.)”

The denial of Berman, Telushkin, Green is no different then those at Bayit Chadash or those connected to the world of Diane Hamilton. The reality is that Gafni has been chased out of many different communities over the years -- and the odds are this sexual predator will not be stopped. His modus operandi is to seek out and sexually manipulate beautiful, brilliant woman. After he is caught he lays low for a few years, during which time he recreates himself and professes his innocence and tells his new community that he is wrongly being accused, even though in the past he confessed to clergy sexual abuse against two teenage girls and many adult women.

Monday, August 1, 2011

The Otherside of Growing Up in Skokie in the 1960s 1970s

By Vicki Polin

Skokie Sexual Abuse Examiner - August 1, 2011

Skokie Sexual Abuse Examiner - August 1, 2011

Please note that the names of those in this story have been changed to protect their identities.

Last year I returned to the Chicago area after being away for over a decade. It’s been a wonderful experience reconnecting with so many childhood friends through Facebook and attending so many reunions and gatherings that would make anyone smile. Sharing so many memories of good times and seeing where the lives of my childhood friends have lead them is truly a pleasure. What we didn’t know was how many of our classmates were being abused in and out of their homes during our childhoods.

I’ll never forget my friend James telling me about how he and Billy were beaten up by two other boys, whose parents were holocaust survivors. The reason why James was beaten up was because his friend was of German descent and NOT Jewish. This wasn’t just a one time thing it happened repeatedly throughout his childhood.

At a reunion picnic I met up with Joanne. When I first saw her I knew she looked familiar, but I couldn’t place her. For some strange reason I asked her if she was still friends with Mary and Darlene. She looked at me in both rage and tears and looked as if she wanted to hit me. She then went on and described how both Mary, Darlene and Kristina would corner her and beat her up for no reason. Her beatings happened almost daily. Even with interventions from school personal the beatings continued. Her family had no option but to move to another community.

The saddest part was the fact in all these cases, those who offended my classmates were people I knew and considered to be my friends. I had no idea this type of bullying was going on.

At gathering of folks that included those of us who grew up on Chicago’s northshore, a former homecoming queen from another school shared how she was being emotionally abused in her home.

No matter what she did or said her father would tell her how ugly she was. No matter what she did or said the emotional abuse never ended.

As young children, my best friend from kindergarten and I used to share our abuse histories, without even knowing what was happening to us was criminal. I’ll

I’ll never forget the day that Sharon showed me the burn marks on her body given to her by her mother who was an alcoholic. You see Sharon was often used as an ashtray when her mother was angry at her. When we were in sixth grade Sharon and several other people I knew started using drugs. I’ll never forget when Sharon showed me how she would shoot up heroin at the age of 11. Sharon also dropped out of high school when she was sixteen.

I will also never forget when Barbara and I first reunited after thirty years. Barbara grew up down the street from me. I was so excited to see her, yet she seemed very different then the last time I saw her. Barbara shared with me that growing up she was being sexually abused by her oldest brother. Ever since she shared the details I kept having flashbacks of how she never wanted to go down to the basement of her home where her teenage brother’s bedroom was. It wasn’t until we were at a party that I saw how much she drank. It was obvious to me that she was never able to get the necessary help needed to overcome her child abuse history.

In high school there were a few classmates who attempted and committed suicide. Looking back and remembering their symptomology, so many of them exhibited the symptoms of children being abused.

Those of us who grew up in Skokie in the 60s and 70s were not exempt from the statistics regarding bullying, physical abuse and the fact that one out of every three to five women and one out of every five to seven men were sexually abused by the time they reached their eighteenth birthday.

Thursday, December 16, 2010

Friday, November 5, 2010

Do Girls Matter? Sexism and Sexual Abuse

By Vicki Polin

Huffington Post - November 5, 2010

Over the last ten years there's been so much emphasis and media attention on cases of clergy sexual abuse

- with the perpetrators being priests, pastors, monks and rabbis - that

we seem to be forgetting that forty-six percent of cases of child

sexual abuse are perpetrated by family members. We also cannot forget

that according to statistics girls get molested two to three times more

often then boys -- or that the effects and long-term ramifications are

just as horrendous as their male counterparts.

Over the last

twenty-six years of my involvement in the Anti-Rape movement I have to

admit that I have been amazed at seeing so many male survivors coming

forward with their disclosures of child molestation. Even Oprah's on to

the male survivor bandwagon, producing two shows on the topic of male survivors of sexual abuse; which will air on November 5th and 12th.

My

concern is that girls and adult women who are survivors of child sexual

abuse seem to be getting lost in this new shuffle. I have also noticed

an altering of history from some survivor groups in which they are

forgetting the roots of the Anti-Rape movement. Advocating for

survivors of sex crimes did not get it's start in 2002, with the Boston Globe's

exposé on the Catholic Church. We cannot forget that if it wasn't for

several brave women joining together in consciousness raising groups

back in the early 1970's, we would have no idea about how many people

were being molested as children, or how many adult men and women were

being assaulted.

Why is it that even in 2010 we want to forget

the value of the feminist movement? If it wasn't for the brave heroes

of the 1970's getting together and sharing personal details of their

lives we would never have been able to offer hope and support to those

who had been sexually victimized. We would not have begun to educate the

public on the issues and ramifications of rape nor would research that

effects more then a quarter of the population of the world have been

started.

How quickly we want to forget that back on January 24,

1971 the New York Radical Feminists sponsored the very first gathering

to discuss sexual violence as a social issue. April 12, 1971 was the

historic moment in which for the first time in history there was a

gathering of survivors -- all women, who created the very first

"speak-out" -- where they shared their personal stories publicly; and

over 300 people attended.

I personally got my start in the

Anti-Rape Movement back in 1985 working for one of the first incest

survivor organizations. During the early years it was mostly only women

who came forward sharing stories of child molestation. For the last 12

years of my work has been focusing in Jewish communities on an

international basis. I have been amazed to see this same phenomenon

happening within the orthodox world. Female survivors of sexual abuse

have been taking a back seat to their male counter part. For every 10

males who come forward, there is only one woman willing to share her

story, come forward and begin the healing process..

I have also

encountered some discrimination at workshops and or with other

organizations that have been popping up in the Jewish world; the leaders

are all male. I have been told that they believe women are too

emotional to be a part of the movement, let alone to speak out publicly.

I understand the cultural differences of the Orthodox world in which it

is frowned upon for a woman to speak or educate men in public for

reasons of modesty, yet why are they not coming out speaking to each

other? Will they really loose value as a person if it's known that they

were victims of a sex cri

--

Vicki Polin

authored this article. Polin is a Licensed Clinical Professional

Counselor and the founder and director of The Awareness Center, Inc.,

which is the international Jewish Coalition Against Sexual Abuse/Assault

Monday, November 1, 2010

Vicki Polin: 2010 Jewish Community Heroes Semifinalist

It's quite simple, Vicki Polin created The Awareness Center eleven years

ago, an organization also known as the International Jewish Coalition

Against Sexual Abuse/Assault, which is dedicated to ending sex crimes in

Jewish communities globally.

Vicki

works within every movement of Judaism, from the unaffiliated to

renewal, reform, reconstructionist, traditional, conservative

communities and all the way to the orthodox, charedi and chasidic world.

Vicki's job has not been easy, because she's been shining a light on

things no one wants to acknowledge as being problematic. Over the last

eleven years Vicki's been threatened, spit on, insulted and verbally

abused in her attempts to mentor and advocate for those trying to use

the legal system to obtain justice. Vicki's resilience helps her to

continue on to educate and protect our communities from sexual

predators, and also offer support to those who have already been victims

of sex crimes. Her personal mission is to offer hope and healing to

many of those who feel they have been tossed aside.

Under

Vicki's direction, The Awareness Center does its best to act like the

"Make A Wish Foundation" for survivors of sexual abuse/assault and their

non-offending family members.

Sunday, September 5, 2010

Tattoo me: Religious markings could actually be a cry for help

By Vicki Polin and Michael J. Salamon

Cliffview Pilot - September 5, 2010

Besides the fact that it’s trendy,

many young adults today feel that having tattoos is a way to define who

they are as a person. But that declaration of individuality could

contain an ominous message, one that requires we all pay attention.

Although once part of everyday popular culture, the trend has blossomed among those from extremely religious backgrounds.

Sometimes it’s a call for help.

In a recent case, a 14-year-old

boy‘s father became livid when the teen had a dove professionally etched

in blue and white on his thigh. The father was understandably upset and

wanted to ground his son for life. He also threatened to sue the tattoo

artist for proceeding without adult permission.

According to his son, he completely missed the point.

“I am telling my father in a very rebellious way that I want peace in

the house,” the son said. “I am so tired of his anger and shouting.”

At a kosher butcher’s shop recently, a teenage girl on line pushed

the hair off the nape of her neck to reveal a small Star of David inked

onto her skin. Who knows what motivated her to tattoo herself with that

symbol at that place? A reasonable guess is that she was proud of her

heritage but did not want many people to see the “art.”

After all, tattoos aren’t permitted in the Jewish faith.

Here’s where it gets sticky:

Self-mutilation is often a symptom of unresolved psychological

issues, usually associated with those who’ve been physically or sexually

abused. In its worst stages, youngsters cut or burn themselves until

they bleed.

Those who’ve done it have said they felt numb or in such severe

emotional pain that the physical pain they cause themselves helps

relieve some of the emotional distress.

No one is saying that getting a tattoo falls under that category. For

one thing, it’s done in one location and, in most places, not

repeatedly. At the same time, research shows that we cannot ignore it as

a POSSIBLE indicator of trouble.

A recent study of 236 college students at a Catholic liberal arts

school found a correlation among sexual activity, tattoos and body

piercing — but none between body modifications and religious beliefs or

practice. One possible explanation is that those who tattooed themselves

were rebelling against their childhood lifestyles.

Over the years we’ve seen victims of abuse move from Torah-observant,

Orthodox households into more secular surroundings. At the same time,

many abuse victims from secular backgrounds have shifted from what they

grew up with and headed on a journey of becoming more observant.

Both groups of survivors have one thing in common: They are searching

for a deeper meaning, reason and or purpose to why they were targeted

to be victimized.

In the Orthodox world, a woman wouldn’t be caught dead in short

sleeves in public, let alone wearing a bathing suit. Yet one survivor,

who was sexually abused by an older brother for four years, beginning

when she was 11, disclosed that she had the words “Kadosh, kadosh,

kadosh” (holy, holy, holy) tattooed in Hebrew on her back in her

thirties.

She deliberately labeled herself, she said, so that both she and the world would know that no one could ever abuse her again.

We’ve encountered all types of ethical dilemmas working with Jewish

survivors of childhood abuse. But this now is a trend that carries

severe implications for those who submit to the tattoo gun. Raising the

ethical stakes, youngsters tend to have various prayers that have great

meaning to them tattooed on their arms, backs, legs and chests.

One had Torah verses inked into her skin: “Hear oh Israel the L-rd is

G-d the L-rd is one”, “Hashem shall bless you and watch over you.

Hashem shall shine the light of His/her face upon you and make you

favorable. Hashem shall raise his face towards you and make peace for

you.”

The Torah often tells us — figuratively — to “write these words on your heart,” not on the vessel that conveys you through life.

Which brings us to another serious drawback:

According to Jewish law, these words are not allowed in a bathroom or

in view of a naked body. One halachic advisor has told survivors to

cover those areas of their bodies when going to the bathroom or taking a

shower. Yet there are times when this is impossible to do, depending on

where the tattoos are.

Growing up Jewish and being sexually abused as a child — especially

in the ultra-Orthodox world — becomes a greater nightmare when no one

believes the survivor or gets him or her the necessary help from a

qualified mental health provider.

All too often, nothing is done at all. Either the victims feel so

much shame that either they don’t tell anyone or it takes years to do

so, or they‘re simply not believed when they do.

As children, and even as young adults, many of these survivors had no

idea how to deal with or process the thoughts and emotions that go

along with being sexually victimized. When a survivor lacks words or is

disbelieved, the emotional pain intensifies. All too often, they turn

to drugs or food as a coping mechanism to anesthetize the pain.

Or they attack the “thing” that caused them pain in the first place: their bodies.

In many ways, people look upon these symbols as cool or hip.

Unfortunately, they can also represent a cry for help, not unlike

certain other forms of self-mutilation. It’s important that those of us

whose loved ones take to the tattoo needle make it our business to find

out the REAL story behind the markings, just in case.

Monday, June 21, 2010

From the Heart

© (2010) by Vicki Polin, MA, LCPC

Originally published in The Awareness Center's Daily Newsletter

Originally published in The Awareness Center's Daily Newsletter

I'm

sharing the following with you, because I know I am not the only person

who has ever experienced what I'm about to share with you. It's a

topic which I doubt has really ever been discussed in detail in any

public venue.

Several

years ago I saw an elderly couple walking in a parking lot of a mall in

my home town. The couple looked very familiar to me, yet I was having a

difficult time placing them. As I got closer I realized who they were.

. . I said, "hi mom, hi dad". They looked at me, said hello and then

wished me a good day as they went on with their day. These were two

people who I spent the first eighteen years of my life with. Though

they are biologically my parents, they are virtually strangers to me.

Today

is my father's 78th birthday. It's such an odd thing to say that I

haven't known my father since he was 47. He's been out of my life for

over 30 years.

I know that I am not the only adult

survivors of child abuse (emotional, physical and sexual abuse) that is

confronted with not knowing what to do, nor how to feel when birthdays,

mother's day, father's day and or other holidays or anniversaries come

around. For me, these types of days often leaves a void of emotions and feelings.

I know that several other adult survivors of child abuse may also need to separate from their families to heal, yet often keep it a secret for fear of being shamed or looked at as being different. I felt that it was important to share my experience in hopes of helping others realize that they are not alone, and to know that they do not need to keep their silence any longer.

I also felt the need to acknowledge my father's special day some how. I guess this note is my way of saying "Happy Birthday Dad".

Friday, June 18, 2010

To Survivors of Incest and other forms of Child Abuse Regarding Father's Day

Father's day is approaching, if you are a survivors of incest, remember

you are not alone. Not all father's should or need to be honored. Just

like any holiday, be kind to yourself. Surround yourself with people

who inspire you to heal.

Remember you are good and always have been. What happened to you was a crime. It's NOT your fault.

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

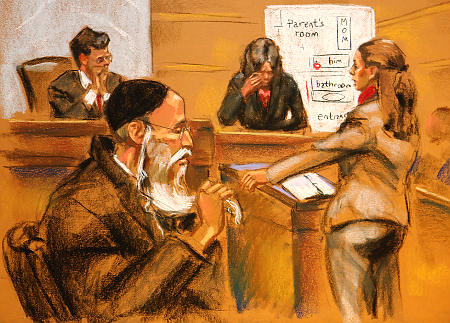

Unprecedented Case Brings Brooklyn Rabbi to Secular Court to Be Sentenced

By Yasmina Guerda

Brooklyn Daily Eagle - April 13, 2010

Brooklyn Daily Eagle - April 13, 2010

Outside Hasidic Realm, Rabbi Lebovits Faced New Trend in Sexual Prosecutions

Brooklyn — As the Vatican struggles with fresh headlines on scandals of

child sex abuse, the Jewish communities throughout the world have been

embroiled in a similar plague. In the last year, Brooklyn’s State

Supreme Court has issued an increasing number of subpoenas to members of

the Jewish Orthodox community in relation to child sexual abuse cases.

Until recently, most of these cases were handled for the community by

the community and entirely within the community.The increase in the number of cases reported to the secular justice system by members of this particularly closed group is the result of a long process: bridges built between secular and religious judicial authorities in Brooklyn, and a strong collaboration between Jewish organizations and the District Attorney’s office through the project Kol Tzedek, Hebrew for “Voice of Justice.” The program has now reached its first year milestone.

He could spend the rest of his life in jail, but he remained silent during the four days of his trial. Baruch Mordechai Lebovits is a corpulent 59-year-old rabbi from Borough Park, in Brooklyn. On March 8, 2010, the day his verdict was to be announced, he arrived in the Kings County State Supreme Court striding behind his two lawyers, his face looking down to avoid the stares of a dozen bystanders outside Ceremonial courtroom No. 1.

Lebovits was followed by five of his relatives and friends. Slowly, more and more of the rabbi’s supporters quietly entered the courtroom and congregated in the benches behind the accused. Soon, two thirds of the seats would be filled with members of the Borough Park Jewish Orthodox community. Interviews with some of these men and women revealed their complete rejection of the charges: that Lebovits molested one of his 16-year-old students in 2004. His supporters were equally unconvinced by the multiple counts of child sexual assault for which Lebovits has yet to be tried. By the end of this year, Lebovits will be judged for allegedly abusing two other children.

Seated 30 feet away from his molester on the other side of the room, the plaintiff Yoav Schonberg, now 22, was surrounded by his father, a few friends, and Kal Holczler, who claims to have been molested by his own rabbi when he was a teenager. Schonberg was the prosecution’s primary witness against Lebovits. He was timid, obviously at odds with himself, and Justice Patricia DiMango had to ask him several times to speak up during his testimony. Speaking haltingly in a frail voice, Schonberg explained to the court that on May 2, 2004, Rabbi Lebovits offered him a free driving lesson. After a few minutes, Schonberg said, Lebovits instructed him to pull the car over, at which point the rabbi unzipped the young boy’s pants and began performing oral sex. According to the Assistant District Attorney Miss Gregory, the same thing happened to Yoav Schonberg, who was 16 back then, nine more times, until February 22, 2005. “It happened many many more times, but my son wasn’t able to remember the specific dates so it is not valid for the prosecution,” explained Yaakov Schonberg, the plaintiff’s father.

When the verdict was handed down, Lebovits did not move. He did not grimace; he did not sigh almost as if he had expected it, despite his “innocent” plea. Among his supporters, though, a few wiped tears from their cheeks and gasped for breath. Many started making calls as soon as they left the courtroom, to keep the rest of the community updated. The jury found the rabbi who is also a teacher at the Munkatch yeshiva (religious school) and the owner of a travel agency in Borough Park guilty of eight of the ten counts in the indictment. The sentence will be read today. For these charges alone, Lebovits faces up to 32 years in prison, four years for each count on which he was convicted. But at least two more trials await the rabbi this year. One of his alleged victims was 16-years-old and the other was 15 at the time the assaults are said to have occurred. “In the community, I’ve spoken to dozens of families who say their children were molested by this man. Dozens! The problem is that half of them don’t want to let it be known, and the other half can’t do anything about it because it’s too late,” explained Yaakov Schonberg, in reference to the five-year statute of limitations that make it impossible for victims to file a lawsuit after they turn 23.

Brooklyn is home to over 300,000 Orthodox Jews – mainly in Williamsburg, Flatbush, Crown Heights and Borough Park — but for decades, prosecutors very rarely tackled alleged child molesters in this community. According to an October 14, 2009 article by Paul Vitello in the New York Times, “of some 700 child abuse cases brought in an average year, few involved members of the Orthodox Jewish community. Some years, there were one or two arrests, or none.”

In the past year, however, according to the Kings County D.A.’s office, 30 members of this community in Brooklyn have been prosecuted for child sexual abuse. Among those 30 prosecutions, half were for misdemeanor offenses, half for felony crimes.

This sudden breakthrough in the ability of the secular judicial system to prosecute sex crimes within this tight-lipped community has been facilitated by Kol Tzedek, the program that Brooklyn D.A. Charles Hynes launched a year ago. Its goal was to build a dialogue between secular law enforcement agencies and Orthodox Jews as well as within the community itself.

Kol Tzedek includes a hotline for victims to report abuse and receive psychological support anonymously until they are ready to go to court. The program also has a prevention component, operated with the help of three Jewish social organizations – the Jewish Board of Family and Children Services, Ohel Children’s Home and Family Services, and the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty.

“It is a very scary issue,” said Dr. Hindie Klein, the psychotherapist who runs Ohel’s Tikvah Mental Health clinic in Borough Park in which several victims of sexual abuse have been treated. Klein is also in charge of Kol Tzedek at Ohel. This social services organization specializes in Jewish communities, provides help in several fields job search, poverty, mental health, foster care, etc, and last year, it celebrated its 40th year of existence. “Many members of the community don’t even know what is and what isn’t considered sexual assault!” Klein explained. “It’s Sabbath, the whole family gets together, and then you notice that this uncle or this neighbor has been playing a lot with your kid, taking him on his lap, touching him affectionately … Where is the line? Sometimes it’s nothing, and sometimes it’s worrying. The first thing that people lack in this community is definitely knowledge on this matter,” she pointed out, stressing each one of her words with both her hands. “But even then,” added Derek Saker, Ohel’s spokesman, who was sitting next to Hindie Klein, “once they know their children have been molested, families won’t always have the right reaction. There’s the fear of the stigma, enhanced by the fact that this is a very close-knit and modest community that we are talking about.”

According to Rabbi Nuchem Rosenberg, an activist who works in Williamsburg to prevent the sexual abuse of children, “If a kid comes home and tells his parents that one of his teachers or his rabbi touched his private parts, parents will have one of these two reactions: they will either slap him in the face and ground him for lying and being immodest, or they will tell him that it was nothing and that he should forget about it.” The general disbelief and/or denial was also noted by Shoshannah Frydman who is in charge of the project Kol Tzedek at the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, a social services agency operating in New York City. “In any community, it is a topic that people refuse to face, and in an insular community, as is the Orthodox Jewish community of Brooklyn, of course, these things tend to be hidden under the carpet even more. They have a different understanding of child protection and criminal justice.” Frydman also said that there was an important lack of information on sexual abuse itself. “People think that if their children were abused, it is going to influence their whole sexuality, or create problems when it comes to finding a wife or a husband.”

An indication of the resistance within the Orthodox community to bringing child molesters to justice can be found in posts from blogger Yerachmiel Lopin, who writes about child molestation in Brooklyn: “A source in Boro Park tells me that [a flyer calling for witnesses to testify against Lebovits and to contact Miss Gregory at the D.A.’s office] was strewn all over his neighborhood on Shabbat morning on November 21, 2009. By noon the flyers had all been removed. … It is striking that this secret activity is being undertaken. One would have thought that given the many children he may have molested the community leadership could easily assure the necessary roster of witnesses.”

“We can’t let things be handled by the community. Our only way out is to turn to secular justice,” insisted Victoria Polin, the social worker who founded the Awareness Center, based in Baltimore, MD. This international organization has been fighting child sexual abuse for eleven years in Jewish communities throughout the world by means of prevention programs and information workshops. Polin’s Awareness Center also helps survivors deal with the consequences of having been sexually assaulted. “So many children end up committing suicide, or falling into drugs… They can end up having very serious health problems because some were abused when they were very young and they had their insides torn; girls can have long-term gynecological issues; others will refuse to go to the dentist during their entire lives because of the trauma of having somebody else put something in their mouth,” Polin said.

In Williamsburg, on November 5, 2009, several newspapers reported that Motty Borger, 24, committed suicide, two days after his wedding. As his new wife was asleep, at 6:45 a.m., Borger jumped from his seventh floor room at the Avenue Plaza hotel. Although no suicide note was found, friends of Borger’s told reporters that, a few days before Borger killed himself, he had confided to his father-in-law and to his wife that Rabbi Lebovits had sodomized him.

“My son hasn’t killed himself,” said Yaakov Schonberg, the father of the abused boy in Lebovits’ trial. “But he spent four years navigating between crack and cocaine addiction, he was unable to get a job, he started stealing money from synagogues to finance his addiction… and of course he was arrested several times for stealing that money. It’s a vicious cycle!” In 2008, Yoav was sent to a rehab center in Los Angeles, CA, but he only stayed there for one month. Since then, even though he still wears his black velvet kippah, and considers himself a Jew, Yoav Schonberg says he has left the Hareidi world: he no longer goes to the synagogue to pray, he shaves his beard regularly and has stopped wearing his hair side curls. His father still has the side curls and follows the dress code of the Munkatch Orthodox sect, but he has also partially withdrawn from its strict rules: “I am under no rabbi. No rabbi tells me what to do now,” Yaakov Schonberg said.

This trend is not specific to the Jewish Orthodox communities, according to Victoria Polin, the Awareness Center founder. “When something this tragic happens, of course, victims will lose trust in their community, and that is why it is so important that secular authorities be there for survivors. Otherwise, they will feel like they have nobody to turn to,” Polin insisted.

District Attorney Hynes, who has spent his whole career in Brooklyn, is used to dealing with leaders of the Orthodox Jewish community. Several times in the past ten years, advocates for victims of sexual abuse have accused Hynes of seeking peace in his jurisdiction by turning a blind eye to the community’s practice of funneling abuse cases through religious tribunals and shutting out secular justice authorities. “But the real problem,” said Jerry Schmetterer, spokesman for the Brooklyn D.A., “was that they just didn’t trust us. We really feel it’s working well now. The fact that the program Kol Tzedek is anonymous is what really made the difference.”

Dr. Hindie Klein who, as the director of a mental health clinic, has received “many anonymous calls from frightened parents looking for information,” said that the reason why it is so difficult for a family to talk to secular authorities is that they don’t know what consequences their call will have. “Will everything break out publicly? Will their family be outcast for something that could possibly have been nothing? They need to know that their call will have no consequences unless they decide otherwise.” According to Klein, as well, total anonymity and privacy is what Kol Tzedek’s strength depends on.

Every Orthodox Jewish community has religious tribunals, composed of three, or sometimes four rabbis. These rabbinical courts, called “Bet Din,” Hebrew for “House of Judgment,” are intended to settle every disagreement within the community and only rarely choose to report cases to secular judicial authorities. “It’s a matter of protecting the community,” explained Yaakov Schonberg. “By handling problems yourself, you prevent the others from knowing about those problems and from using them against you.” Breaking the rule and reaching out to secular authorities when there is a problem within the community, according to Schonberg, will get you excommunicated more often than not. Excommunication means that someone will not be allowed in any synagogue of the community, his/her children won’t be accepted in any yeshiva, and shopkeepers will refuse to do business with that person. “The pressure on the family is huge!” added Yaakov Schonberg.

In Lebovits’ case, for instance, the prosecutor presented evidence that pressure had been applied to the victim by a local religious court to persuade him to drop the charges. One of the defense attorneys’ witnesses was Rabbi Berel Ashkenazi, a friend of Lebovits’ who had come to court to testify that the victim was a “con man” as defense lawyer Arthur Aidala described him and that he was not worthy of trust. Ashkenazi, 44 years old and the father of nine children, had also been the plaintiff’s teacher, from October 2003 until June 2004 at Spinka religious school in Borough Park. Assistant D.A. Miss Gregory brought to the trial copies of a letter sent by one of Borough Park’s rabbinical courts to Rabbi Ashkenazi. It stipulated that Ashkenazi, to whom Schonberg had gone for assistance, should offer financial support to Schonberg to treat his drug addiction, and help him to a rehab center “if and only if” he agreed “to drop the case in a non-Jewish court.” This is just one of the many types of pressure a rabbinical court can apply to the community it rules in, if they are suspected of committing “Mesirah,” Hebrew for “informing.”

In the courtroom, after Assistant D.A. Gregory asked him to do so, witness Rabbi Ashkenazi explained what the concept of “Mesirah” meant for the Orthodox community: “A Jewish man is not allowed to go to a secular court against another Jew without the permission of his rabbi,” Ashkenazi explained. Then, Gregory continued: “And could you tell me what happens if someone does not follow that rule? Would that person be stigmatized for not doing so?” After a few seconds of hesitation and stammering, Ashkenazi replied: “If someone doesn’t do so, the rabbi would have to talk to him.” When the questioning was over, the witness swiftly got up from his seat and walked rapidly towards the exit of the courtroom, looking straight ahead, avoiding the stares of the audience.

The plaintiff’s father said he had also been under pressure during the month before the Lebovits’ trial began. “As soon as the date of the trial was officially announced, I received calls from everywhere, even from Israel!” He said people were calling to ask him to drop the case and go to a religious tribunal instead. “But you have to understand, rabbinical courts used to mean something,” Yaakov Schonberg said. “They used to have real authority and real moral superiority in the community. Now it has become a business, a way to make money!” Schonberg explained how thirty years ago, there used to be only one Bet Din in Borough Park and another one in Williamsburg, and how now, there were dozens in each neighborhood. “Now, it’s usually three young rabbis who know very little, fresh from rabbinical school, and they call themselves rabbinical court!” he said, gesticulating vigorously. He paused and added: “They don’t have to be approved by anyone, there is no election, no nomination, no validation whatsoever. They just open an office, put a sign that says “Bet Din,”… and charge each plaintiff $100 an hour!”

Rabbi Nuchem Rosenberg, who has for over ten years been strongly encouraging victims to bring sexual offenders before a secular court, said he was now considered an outcast in Brooklyn. He was excommunicated two years ago after he launched a hotline to “teach victims and their relatives how to react when they are confronted with a sexual abuse situation.” “Today, there isn’t one synagogue in this borough that will accept me, even the most liberal ones,” Rosenberg said. “Such pressure has been made on every rabbi in Brooklyn that now I have to go pray in Manhattan, and even there, my rabbi received several calls from leaders in Williamsburg asking him not to let me in anymore. But he answered ‘No one rules in my synagogue but me!”

For Yaakov Schonberg, the fact that sexual crimes in the community are perpetrated by rabbis, teachers and other community leaders is “what’s worst about it. … These people have a very high stature, everybody knows and respects them.” According to Lebovits’ defense attorney Arthur Aidala, Lebovits’ son, Chaim, is “a multi-millionaire,” who has “businesses all over the world,” a fact that Schonberg uses to describe how powerful Lebovits is, according to him.

“I do not know anything about money pressure or any other kind of pressure,” said Dr. Hindie Klein, the director of Ohel’s Mental Health clinic in Borough Park. “What I do know, and this is the case in every community, not just in the Jewish Orthodox world, is that sexual abusers are generally in a position of authority over the child.” She added: “It can be rabbis, but also teachers, camp leaders, or family members. The thing is that when a rabbi does it, it has a more dramatic resonance, because they represent this moral authority, and they are supposed to know better.”

One of the big problems judicial authorities face when dealing with the sexual abuse of children in Jewish Orthodox communities lies in defining the extent of it. Looking only at the cases reported to secular authorities, the problem would be almost non-existent. Jewish advocacy groups for sexual abuse victims argue, however, that molestation in the Hareidi community is heavily underreported to secular authorities. According to Victoria Polin, from the Awareness Center, “it is generally considered that 84 percent of child sexual abuse cases are never reported to the police. But in the Jewish Orthodox community, we believe the rate is around 99 percent … And this is an optimistic estimation!”

According to a study issued in 1988 by the National Institute of Mental Health, the typical child sex offender molests an average of 117 children. “There aren’t many sexual abusers in each community,” observed Rabbi Nuchem Rosenberg. “But even if there’s only one or two in each neighborhood, the problem is that it’s easy for them: they have all the children at their disposal.”

No organization seems to have kept any record or statistics concerning child sex abuse in the Jewish Orthodox community. The Metropolitan Council offered support, long before Kol Tzedek, to sexual abuse victims “but [they] never ever reported the number of calls [they] received on a file or anything. [They] have absolutely no figures concerning the percentage of children being sexually abused in our communities,” explained Shoshannah Frydman, head of Family Services at the Met Council.

Which is why, Dr. Hindie Klein from Ohel said, Kol Tzedek is such a step forward. “They have done a fabulous job at the D.A.’s office, encouraging victims to talk. They are extremely culturally competent and they keep records of the calls. This is going to help evaluate the extent of the problem in depth.”

Both the Met Council and Ohel Children’s Home organize regular meetings and workshops with Jewish Community Council’s directors and other community leaders in schools and synagogues, as well as with social workers throughout Brooklyn. “The aim of these meetings is to give information on what sexual abuse means for a victim, how to handle the trauma, how to identify a sexual offender in the community...,” explained Shoshannah Frydman.

While the Kol Tzedek hotline’s goal is to guide survivors mainly towards a secular legal process, the Met council, Ohel and the Jewish Board focus more on prevention, treatment, awareness, specific training of social workers within the community, outreach and financial support both for sexual abuse victims and for perpetrators. “There are a number of skilled clinicians who are providing treatment to the victims in our Borough Park counseling center,” explained Faye Wilbur, licensed social worker and coordinator of Kol Tzedek for the Jewish Board. “Our therapists are especially trained in working with trauma, and are members of the Orthodox community.” Apart from Kol Tzedek, the Jewish Board has, since 1995, been taking part in another program to fight the sexual molestation of children in Borough Park. Called “Be’ad HaYeled” (Hebrew for “On behalf of the child”), its goal is to “educate the community on the signs and symptoms of abuse and neglect,” explained Jo Gonsalves, director of communications for the Jewish Board.

Ohel Children’s Home and Family Services also tried to tackle the issue repeatedly. In the past years, this social agency produced several videos with survivors of child sexual abuse testifying on camera, and appealing to other victims to come forward and search for professional assistance.

Kol Tzedek is the program of which the purpose is specifically to encourage sexual abuse victims to press charges in non-Jewish courts. However, it is not the Brooklyn D.A.’s first attempt to address issues that touch specifically the Jewish Orthodox community, nor is it the first attempt to address specifically the issue of child molestation in that community. A domestic violence program, called Project Eden, and an additional project to fight drug addiction, were launched several years ago. But more importantly, in 1997, Ohel had already partnered with the D.A. to create the Offender Treatment Program. Its aim, as its name clearly suggests, was to treat child sexual abusers who were members of the Orthodox community. But the program is now defunct. According to an article published in 2000 in The Jewish Week, the program treated 16 sexual offenders. Eight had gone through the secular criminal justice system and had been assigned to treatment. The remaining eight were also in treatment, but their cases had been handled by local Bet Dins and had never reached New York criminal courts. After a few months, the program died and it took the Kings County D.A.’s office more than ten years to come up with a new system. “It is essential to have a program that is respectful of the nuances,” explained Faye Wilbur, the counselor and social worker in charge of Kol Tzedek operations for the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services. “The program’s partners have staff that speak the language of the community, literally and figuratively.” The importance of this factor in building trust in secular justice was also stressed by Derek Saker, from Ohel Children’s Home and Family Services: “When you’ve been through such a horrendous experience, the last thing you want is to talk to people who do not understand where you come from,” he said.

The Kol Tzedek hotline welcomes callers Hebrew or English. The phone is answered by a full-time licensed social worker specialized in the needs and conventions of the Orthodox community. “Should a caller want to file a prosecution, they will then be taken care of by the team of 18 prosecutors in the Sex Crimes Unit with similar specializations,” said D.A.’s spokesman Schmetterer. “The final goal, of course, is to have them press charges, because it is the only way for us to fight child sexual abuse in the area. But we never push them, we let them go through the process at their own pace. It’s all about building trust.”

* * *

After only one year of existence, Kol Tzedek still has to prove its long run efficacy. Brooklyn D.A.’s spokesman Schmetterer made it clear that “for now, there are no plans to expand the program,” although he acknowledged that “obviously, with more resources, [they] would be able to do more.”

However, at the beginning of March of this year, the state granted the Met Council $500,000 for the purpose of intensifying its prevention program throughout the 25 Jewish Community Councils in New York City, nine of which are located in Brooklyn.

The funds were requested by Brooklyn’s Democratic assemblyman Dov Hikind, and are part of a bigger budget, also allocated in March 2010, and dedicated to abuse awareness and action in other communities. Hikind has made the fight against child molestation in the Jewish Community the signature issue of his term. In fact, it was partly in response to one of his weekly radio shows, in the summer of 2008, that Kol Tzedek was launched a year ago. On his radio program, Hikind several times prompted victims to report to competent secular authorities what had happened to them, and, according to him, he received dozens of private calls from survivors every week.

How the $500,000 will be spent to fight child sexual abuse has yet to be determined. According to the Met Council, most of it should go to prevention and educational programs in Borough Park, the neighborhood which carries the largest Jewish Orthodox community outside of Israel.

“We feel we are getting a lot of support from the local councils, the schools, the synagogues…” noted Shoshannah Frydman, from the Met Council. This observation is shared by most children’s advocates: things are starting to change among members of the Orthodox communities. “We are now facing what the Catholic church faced ten years ago,” said activist Rabbi Nuchem Rosenberg. “Awareness keeps growing day after day. It’s going to take some time, but we are getting there…,” he added. And for Ohel spokesman Derek Saker as well, the struggle has only just begun: “Curbing this issue is going to take a long, long process, and there still needs a lot to be done tremendously!” confirmed Derek Saker, at Ohel.

Still, “five years ago, if you Googled ‘pedophilia and orthodox Jews’, you would’ve only gotten results for anti-Semitic websites,” noted Victoria Polin, from the Awareness Center. “Now, you get respectable organizations, reliable reports, specialized advocacies, blogs maintained by members of the community itself.” And this transformation was also noticed recently by Yaakov Schonberg, the father of Baruch Lebovits’ young victim: “Two years ago, if I had walked into a synagogue after Lebovits’ “guilty” verdict, everybody would have been very hostile for attacking such a well-respected rabbi. But now, it’s the opposite: I’ve been considered as the winner, I’ve been welcomed as a hero!”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)